Hide and Seek

Homo Sapiens has existed for 200,000 years. Written history started 5,000 years ago. So what on earth were we up to for the other 195,000 years?

It’s fair to say that I’m no anthropologist. I couldn’t tell a Denisovan from a Australopithecus. Frankly, I’m not sure I’d back me to tell a tibia from a fibia if you stuck a gun to my head. If you’ve watched the 3 Body Problem recently you’ll have seen a character referencing the Fermi Paradox, which states that the universe is so unimaginably large that statistically there must be other intelligent life out there. In which case, where the hell are they? It is more commonly known as the Great Silence. It is a tantalising thought, but I feel that the more intriguing one is the silence from our own past. Humanity has been around in its current form for a couple of hundred thousand years, but only for the final sliver of that have we got around to inventing writing and keeping records. Masonry, sculpture and painting were all practised for much longer, but still the exhibits in the gallery of prehistoric human endeavour are pretty thin. I don’t think that’s because we didn’t make them, it’s because they have been obliterated by deep time.

Scientists are daily exploring deep space and the trenches of the oceans with ever more sophisticated methods, firing pulses out into the blackness, waiting for them to bounce back to us with information of their latest discovery. This seems much less possible with the past. Instead we have to wait and hope that archeological digs will cough up answers, often to questions we hadn’t thought to ask. Even then, there are so many elements of life as a human being in the deep past that we can almost certainly never know. Much of our own identity is an enigma. Whatever copious information we may have about the actions of the human race, it is all front-loaded into recent history. Common sense would suggest that the deep past didn’t contain any Pablo Picasso’s, Stevie Wonders, Marie Curies or Malalas. But we can’t possibly know for certain…

A terrific and simple fact that will lead any reasonable mind to malfunction is that by the time Cleopatra became queen, some of the pyramids had been standing for 2,000 years. Ancient history existed during ancient history. Our museums contain artifacts of civilisations from ages beyond that: 4,000, 6,000, 10,000 years ago. In Turkey, the Gobekle Tepei site is a place of devotion - probably created by nomadic hunter-gatherers - that is at least three times older than Stonehenge. Even at that time this wasn’t a rudimentary megalith Duplo set thrown together with nothing but brutish force and unthinking belief. It is decorated with remarkable skill, deftness and craft by people who were just like you and me. Head into the caves at Lascaux and you’ll see drawings of animals that far outstrip many modern artists in their direct capture of the essence of life. Without wanting to romanticise early man, these were practical, capable people who when they weren’t making remarkable art in difficult to reach places were chasing down livestock and foraging expertly. Of course their life presented challenges, will have contained disease, high child mortality, a low life expectancy. But I wonder on the quality of that life, the richness and the wonder that they enjoyed in the time that they weren’t hunting.

What stories did they tell? What did they aspire to? Who did they think they were and how did they get here? Did they share jokes? Did they make music? Did they gossip?

Like I said, I’m no anthropologist and it’s easy enough to draw simple conclusions - take what we know of hunter-gatherers who exist now and map it onto the past. Yet there is something remarkable about the fact that I can be here in my electrically lit, gas-heated, well-insualted house typing this to you via the internet while at the same time there are countless groups of people all over the world who are living life in a way not to dissimilar to human beings tens of thousands of years ago. Most of them have some sort of relationship with the modern world and that is fascinating of itself. We are all of us, the human race, experiencing different presents. You could argue some of us are living in the future while others are living in the deep past.

I sometimes find it easy enough to spot when I’m out on the road gigging. Van der Velde’s Inverse Law of Cultural Development is that for every 20 miles you go from a major urban centre, you regress a decade in attitudes. This is not scientific. It is, frankly, anecdotal bollocks. But any comic will tell you about shows they have performed at where it has felt like they are gigging in 1983 if Brexit had already happened and Britain had lost the Falklands War. Of course there are many long journeys into the wilds of the UK that result in a warm welcome and kind, enlightened minds (hallo Fishguard, Millom and Salcombe), but even in this developed country, you’re only a few B-roads from a different way of doing things, a different way of looking and being. Not the deep past perhaps, although our country is dotted with barrows and earthenworks, castles and forts that pock-mark the landscape to describe it’s age. While a short journey in a modern country shows the different paths that groups of humans choose to walk down through time, a global perspective reveals an even greater disparity in experience.

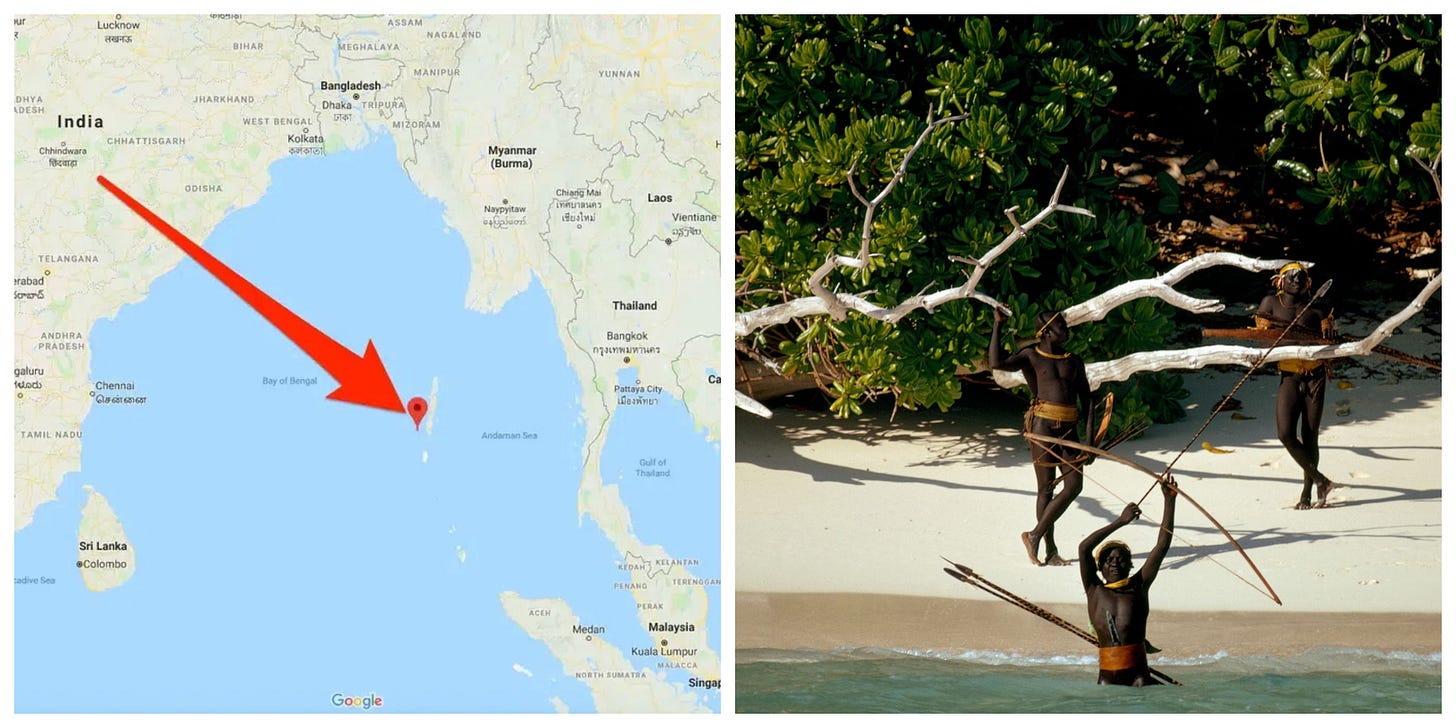

The people I cannot stop thinking about are those who don’t know we’re here. Or even do know and don’t want anything to do with us. I’m thinking particularly of the people of Sentinel Island in the the Indian Ocean. As far as we can tell the hunter-gatherer people who live on this speck of land have remained almost uniquely untouched by the outside world. They first appear in any record in the late 18th century, when a passing ship belonging to the East India Company noted lights on the shore and speculated on the human settlement there. They didn’t explore further as they had bigger fish to extort. Over the following 250 years the islanders have only experienced the briefest contact with the outside world and it is both baffling and disquieting. At first islanders would hide from anyone making landfall. Only in 1880 was any direct contact made and it makes for depressing reading. Maurice Vidal Portman, a colonial administrator to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands - very much the equivalent of an assistant sub-data analyst for the British Empire - kidnapped an elderly man, a woman and four children. The adults soon perished and the children were returned to the island with some ‘I’m-sorry-we-traumatised-you’ gifts. It is hard to know if this cruel, patronising and pointless act influenced the behaviour of the Sentinelese after this or it was innate in their culture.

After this event, any visitors to the island who did encounter the Sentinelese were viciously attacked. Some were killed. Even unlucky seafarers who were wrecked on the island ended up with their throats cut. Anthropologists and members of the Indian government, predominantly arriving with the aim of protecting them, ended up retreating under a volley of spears. The Sentinelese seemed to want the entirety of existence to leave them well alone. Only in 1991 was peaceful contact able to be made, by the Indian anthropologist Madhumala Chattopadhyay. She has advocated that the only good solution for these people is to be left alone. It makes sense for their own survival. They don’t need Sky TV, smallpox or the Bible and none of us need a well-sharpened arrow in the buttock. But even on the other side of the world I can feel the temptation for us to return to the island.

Who do the Sentinelese think we are? Perhaps that’s an arrogantly self-regarding question and I should be more interested in who they are. I am, but I would be surprised if their simple way of life contained anything more than a local variation on the riff of fertility idols, ancestor worship, prostration before the sun and self-aggrandisement at their own identity. I don’t mean to sound like a snooty colonial scientist. I find the variety of traditional believes as fascinating and valid as any other mainstream conception of the universe. Part of me does think “oh goodie, another unique human prism to view the world through.” But their view isn’t vast rolling plains, the fizz and pop of jungle life or the modern metropolitan city. It is a vast, unnavigable blueness. Unchartered either by choice or tradition or lack of ability. Ignoring encounters that may have occured before the 17th century, their interaction with the outside world has been viewing people travelling in strange crafts upon the sea and in the air. On arrival they ask for aid, seek to examine or attempt to convert them. They respond with one part disinterest to four parts homicidal violence.

Do they think we’re aliens? Bad spirits? Ghosts? Monsters? Since their community is so small, I wonder if curiosity has been evolved out of them? Has their ever been a Sentinelese person who suggeted they contact the outside world? Invite in the next visitor? If there was, perhaps they didn’t last long. It’s incredibly self-centred, albeit with a very large centre, to think that they do not know of us: of The Beatles, Shakespeare, Lao Tzu, Simon Bolivar, Marie Curie, Pele, Elizabeth I, Beethoven, Rembrandt, the Olympics. Years ago the Sun (*spits like a old Yiddishe grandmother remembering a particularly hated SS officer*) ran a story where they tracked down the last man to have not heard of David Beckham. He lived in rural Africa. They gifted him a Man United shirt with Beck’s name on it. Compared to the Sentinelese this guy seems like a sophisticated worldly renaissance man.

Were ancient homo sapiens like these people? They probably weren’t as aggressively misanthropic, but perhaps there is a purity to the simplicity of their life. On reflection I suspect that the people of Sentinel Island are actually more rudimentary than many of the people roaming the Earth between 10,000BCE and 200,000 BCE. They are confined to a tiny island, rather than the Eurasian Steppe, North and East Africa or East Asia, filled as all three are with a variety of bounties. They will have been unable to or rejected trade. I was delighted and amazed when I first learned about Viking warriors working as bodyguards in the Byzantine court - globalised employment taking place over 1,000 years ago. There is more than enough evidence that trading networks of depth and sophistication across a large area existed at least 5,000 years ago. Considering the skill of some of the artwork discovered tens of thousands of years ago, why can their not also have been skilled ancient explorers, traders and scouts? There may only have been about two million people on the planet 50,000 years ago (about the population of Chicago) but there is every chance they were teeming all over it like industrious ants with busy opposable thumbs.

I’m making guesses on the infrastructure needed for these people to have created the foundation of their roaming societies, but I also wonder on just how much like us their were. I remember my Dad telling me about how as a ten year old he would contemplate about about bringing Julius Caeser into the present day to see what he would make of it. For me it’s a draw between him being tongue-tied by wonder, descending into a psychotic episode or immediately running to be US President. Yet the fundamental truth that if you’re a homo sapiens you have the same mental (it not cultural or technological) hardware remains. If we took someone from the past and dropped them in the present could they convcieve of it? If we travelled back and met them, could we explain our world to them. That is why I will (spoiler incoming) defend to the death the enormous swing made in the final act of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. Indy meeting Archimedes was an enormous thump in the solar plexus for me - two men who shared a curiosity about the world, an ingenuity of practice but from unfathomably different times still able to communicate. Briefly. What if we turned the dial far further back…

How would we find homo sapiens that were much more recently separated from their fellow hominids thinking about their identity? Just what would their perception of the world be? What would it mean to live on the very edges of time?

The likelihood is that it would all be bound up in worries about hunting, fishing, foraging and roaming. You can only talk shop so much though. There must have been times when these people - us - lay around a fire, sharping their blades and fixing their tools when they made each other laugh, danced, sung and played games. If these were similar to anything we have now, that would be fascinating as would it be if they were radically different. Either way, if ever Doc Brown appears at my door, wild-eyed and enthusiastic, I’m not sitting in the DeLorean to give inspiration to Chuck Berry or kill Hitler (sorry Mum.) I want to go right back to the start, pop open my prehistoric phrase book and see if anyone fancies a game of Stone Age Uno.

A fair whack of the inspiration that came from the enormous conjecture in this Substack came from the book I’m reading at the moment, Nomads: The Wanderers Who Shaped Our World by Anthony Sattin. It’s properly brilliant and I hugely recommend you read it.